Mount Mansfield Electric Railroad

The Little Railroad That Could … For a While

The original story, The Little Engine That Could, is an American folktale that became widely known in the United States after publication in 1930 by Platt & Munk; however, many have concluded that the story belongs to no single author but in the realm of folk literature. The story is used to teach children the value of optimism and hard work. Jim DiClerico, Docent and Board Member with the Stowe Historical Society, builds upon the title of this piece of folk literature to tell the story of The Mount Mansfield Electric Railroad.

Most visitors to Stowe, as well as some locals, likely don’t know that a railroad once served the town. No rails can be seen and no rail bed (unless you know where to look). No rail crossings with familiar X-warning signs. No stations, no car barn, though one once occupied the Stowe Mercantile space on the lower level of the Depot Building.

Introducing The Mount Mansfield Electric Railroad: A single-track affair that ran for 12 miles between Stowe and Waterbury from 1897 to 1932. But was it a railroad or a trolley? Yes, it ran on rails. But labeling it “railroad” takes a bit of hyperbole. Anyone familiar with the trolleys that ran or still run in some urban areas will recognize our little conveyance: Cars running singly, not in trains.

The MMER owned three passenger coaches, two “freight motors” (box cars), an open flat-bed and a double-ended snowplow. All were self-propelled, drawing electricity from an overhead wire by way of “wands” that stretched from the roofs of the cars. Exiting the cars’ motors, the direct current moved to a rail and thence back to its source; copper wiring connected rail segments to complete the circuit.

How did the MMER come to be? Let’s start with a wide historical view. American railroading was booming after the Civil War. Our first transcontinental railroad, begun while the war raged in 1863, finished with the driving of the Golden Spike in 1869 at Promontory Summit, Utah. By then, Vermont’s legislature had chartered a railroad to run between Waterbury and Morrisville.

An electric future dawns. Frank Sprague, once an employee of Thomas Edison, had developed the concept of electrically-driven railroads. His first line began service in 1888 in Richmond, Virginia, and Stowe’s answer was at hand! It took nine years to get our project going, though. Numerous issues needed to be addressed. The route needed to be laid out and right-of-way acquired. A power plant and a car barn needed to be sited—and here some disagreements between Waterbury and Stowe arose. But before any of that could be nailed down, the big gorilla in the room (or moose, if you prefer) had to be satisfied: Money.

Funding the project. From the outset, the railroad inspired support from both the general public and commercial interests. No one enjoyed traveling or shipping goods on the winding, rutted, rocky, often muddy road between Waterbury and Stowe. So the MMER tried selling shares in the railroad. Of three thousand shares issued at $100 each, only 100 were sold, many to business owners needing a better way to move goods. The Burt Brothers of Stowe, owners of a large lumber business, bought 10 shares each, as did P.S. Pike, a Stowe manufacturer of butter boxes. Demonstrating the commercial potential of the line, the Burts published a list of goods shipped annually from Stowe at the time (by the carload): maple sugar (8), potatoes (5), tanning bark (6), livestock (25), butter (60), butter tubs/boxes (150), lumber (300).

The most essential funder was Arthur M. Soden, a Boston businessman who put up more than half the $200,000 needed to build the railroad (about $1.2 million today). Stowe bonded $40,000 and the rest of the projected cost came from stock sales and other sources. Soden stayed a supporter for the rest of his life, ending as president of the line. Sidebar: Soden once owned the Boston National baseball team, forerunner of the Boston, Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves.

Building the line. When 1897 dawned, plans and funding for the MMER were in place, as were plenty of immigrant Italians ready to do the heavy work. But making the line a reality proved daunting as funding it. Difficult grade challenges loomed. Sometimes less than optimal solutions were chosen to solve them. One involved cutting through a clay bank north of Waterbury instead of going over a nearby low hill. Walls of the cut were made with little concern for the effect of heavy rain and snow melt…and not enough attention to good angles for stability. With great regularity, the walls collapsed, inundating the tracks and halting service.

The ravine of Bryant Brook in Waterbury Center posed another challenge, one handled with eye-catching success. A 735-foot-long trestle spanned the gorge, standing 76 feet tall at its highest. Called “matchstick” construction, the trestle consisted of timbers 8 to 12 inches square. Some matchsticks! The structure could handle a heavy steam engine pushing loads of rails and crossties as track was laid south-to-north. Sometimes other vehicles sought to use the trestle, including motorcars (one driver possibly inebriated) and a horse-drawn farm wagon. The latter fell from the trestle, killing the driver and one of his horses.

Powering the line meant building an electricity source, and issues of political control and funding arose over locating it. Eventually, a coal-fired plant was built at Shutesville, just inside the Stowe line, instead of at a more logical, midway site in Waterbury Center. Thus power near Waterbury proved barely adequate for running the equipment. A battery house built there in 1908 somewhat alleviated the problem, and further relief came in 1912 with power from Morrisville’s municipal plant. The rotary converter needed to turn alternating current into the line’s required direct version resided in the Stowe car barn. This part of the MMER project may have accelerated the electrification of Stowe.

Good times and bad. The MMER proved popular at first, managing small profits from passenger and freight fees. Three to five cars a day each way let riders forgo slow and kidney-rattling coach trips over the primitive Stowe-Waterbury road. Commercial enterprises liked the faster and smoother way to move goods between the two towns. Carrying mail benefited both postal customers and the line’s coffers.

But when the State of Vermont paved route 100, attracting more and more automobile and truck traffic, the line’s usage steadily declined. Bankruptcy was declared in 1907 but the reorganized company continued to suffer losses. For example, monthly passenger revenues dropped by half between 1912 and 1920. The line went out of business in 1932.

When Rail Came To Our Front Door: 1897-1932

The Mount Mansfield Electric Railroad by Jerry Chase

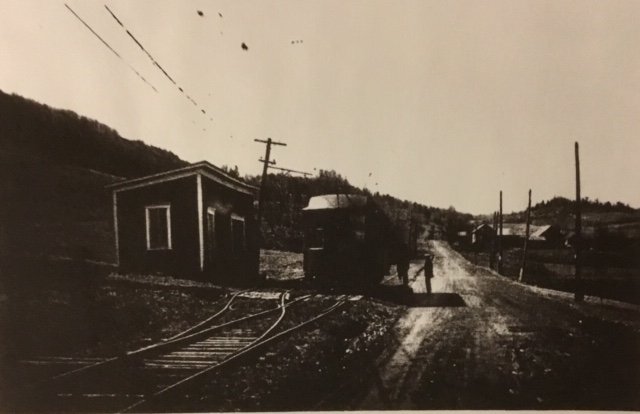

Above is a faded, early view of a Waterbury bound car stopped at the turn to Moscow, a few miles south of Stowe Village. The dress of the three women dates the picture to the early 1900's and they were standing in the road that is now Vermont Route 100. The Mount Mansfield Electric Railroad by Jerry Chase is on display at the Stowe Historical Society.

In 1849, the main line of the Central Vermont Railroad passed through Waterbury, a tantalizing 12 miles from the resource rich town of Stowe, VT. Access to the transportation revolution, access to the markets of the cities of New England and beyond was hampered by reliance on a narrow dirt road, and not a very good one at that. But this was a creative era, and experiments in light rail or interurban trolleys were ongoing in the 1870’s and 80’s. In 1883 a protégé of Thomas Edison named Frank Springer developed a system that was a good match for the challenges facing Stowe in improving the movement of goods to the Central Vermont Railroad.

Features of the railroad eventually built: passenger and freight cars with their own on-board electric motors, a single energized overhead wire, which supplied electricity through a contact power pole down to the electric motors, and a fixed coal and wood fired plant on the east side of Shutesville Hill.

Steam Powered Power Station

The Mount Mansfield Electric Railroad was powered by a steam electric generator located on the Stowe side of Shutsville Hill near Neal Chapin’s place (chainsaw carvers). The telephone pole on far left supports an energized wire for the freight motor, which delivered “reefer”. The original car barn is to the right.

Originally the power source for the station for the Mount Mansfield Electric Railroad was wood or coal fired. The plant closed in 1908 when Mt Mansfield Electric Railroad (MMER) began purchasing power from Morrisville Water & Light to charge the overhead wires. The overhead wire, that runs the length of the track, was the source of power for the on-board electric motors that drove the cars. There were 3 or 4 telephone wires attached to support poles: one for MMER dispatch and the others for the local telephone company. The Refrigerator car was owned by National Dispatch Line, and presumably pressed into service to supply coal to fuel the boilers. This car was designed to travel the Vermont Central Rail Road and had no motive power, unlike MMER cars.

Moscow Turn

The picture on the left, c. Spring 1932, is at the turn to Moscow and close to where Stowe Maple is located today. Notice the change in Rt. 100 from the early 1900's to 1932.

Snowblower

Snowblower for the Mount Mansfield Electric Railroad

Want more? The archives of the Stowe Historical Society include several books and articles about the MMER. These contain official records, anecdotes and statistics in addition to a wealth of photos, maps and drawings. Come peruse all this and enjoy an exhibit of models of the line’s rolling stock as well as artifacts such as a seat from one of the passenger coaches.

traveling north up Shutesville Hill

MMER trolley traveling north up Shutesville Hill to Stowe during the winter, c. 1930

MMER freight motor #2

MMER freight motor #2 pulling a Canadian National freight car from Waterbury to Stowe

MMER between Waterbury & Stowe

Map showing the route of the MMER between Waterbury and Stowe (1897-1932)